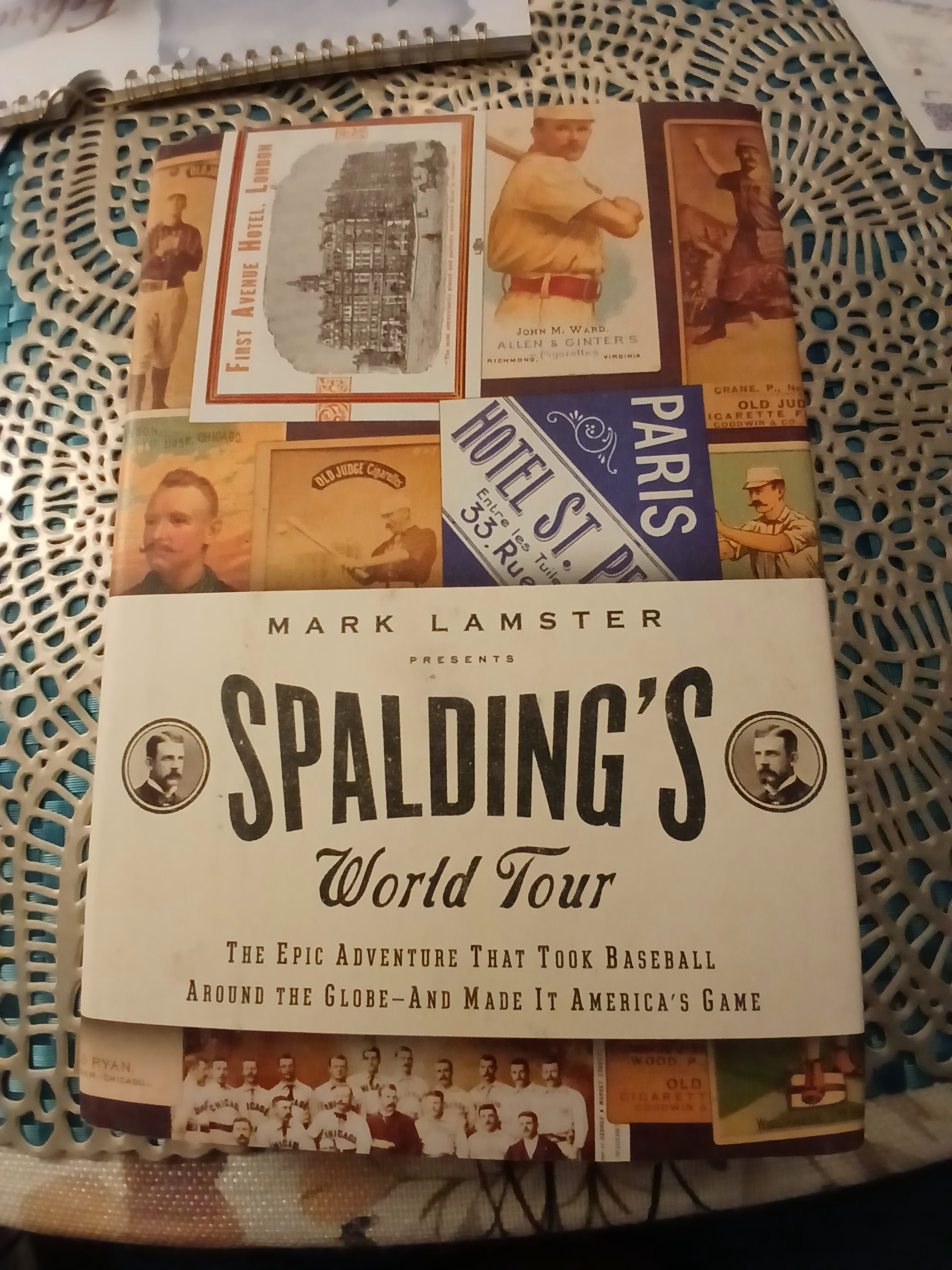

I just finished reading a very interesting baseball book. The book’s characters are real, they played professional baseball circa late 1800s to early 1900s. The book’s title, “Spalding’s World Tour” references a real person, Albert Spalding, the former professional baseball player turned owner and sporting goods magnate. The book is a geography lesson, a history of world’s transportation system, and is about a seemingly half-brain idea that turned out to be a very successful campaign. The campaign, as the subtitle suggests, was to introduce the world to the game of baseball. Written by Mark Lamster, the subtitle reads, “the epic adventure that took baseball around the globe – and made it America’s Game.”

In every line of work, in every business that has been in existence since the beginning of the United States of America, you have players, managers, owners, and visionaries. The players play, the managers manage, the owners own property, and the visionaries dream. Albert Spalding was a player, a manager, an owner, but was best suited as a visionary. From his days running a professional baseball club in Chicago to his sporting goods company that is still in operation some 150 years later, Spalding often thought outside the box of normal business operations. And he was more often right than wrong. And here comes the book with the tale of Spalding’s idea to introduce baseball to the world and the players who went along for this historic ride.

Newspapers, telegrams, speaking engagements, receptions, recitals, about 50 games played, and some 30,000 miles of travel all add up to how Spalding’s vision of introducing baseball to the world became a reality. Starting with the cross country train ride from Chicago, playing exhibitions along the way in Colorado and California, Spalding’s World Tour would dead end on the US portion of the tour on the West Coast. This is where they hopped a vessel west to the Island of Hawaii, then the continent of Australia to meet dignitaries and play baseball exhibitions. From Australia, Africa was next up, and with exciting tour stops in Egypt, the players got to explore the Egyptian culture and play a game in front of the Great Pyramids. More receptions, more champagne toasts, more travel nightmares via train, horse and carriage, and just about any means necessary got the men, known often in the book as “tourists,” to the European continent. Stops in Italy, France, England, and Ireland to play and promote baseball, drink and eat the local customary delicacies, and be the wonderful baseball ambassadors Spalding had envisioned.

The travel and accommodations were not always top shelf. The weather was a factor during a lot of the exhibition game locales. There was, on various stops of the tour, a general lack of understanding of the game of baseball. The boat rides across the English Channel, the train rides through Egypt, and every other means of transportation are all documented brilliantly in this book. As are the hotel stays, the cities and towns the tourists stayed in, the royalty who greeted Spalding and his baseball ambassadors, and the fields the tourists played out their exhibition games on. This book is a wonderful history lesson of life in the world pre-1900. Industrious cities like Cairo, London, Sydney, New York all started to take form and carry the weight of their region for decades and centuries to follow. I loved reading about all these incredible stops along the way from Chicago to Los Angeles, from Hawaii to Sydney, from Cairo to Paris. It was just an amazing read and so fascinating to learn what life was like a century or so ago here in the US and abroad.

Mark Lamster’s “Spalding’s World Tour” is not an easy read. Not because of the subject matter (s) but mostly because of the 5 and 10 and 15 dollar words Lamster uses in the book. Plus, you have all this incredible local and regional dialect once you read about Hawaii or Paris or Egypt that you have to pause to ask “ok, what does that word or phrase mean?” You have to take your time reading a book like this because if you skim over the big words, you will miss out on a number of important contexts that are vital to the story. Heck, get a dictionary out if you need it. In addition to the great tales, the book is peppered with some amazing black and white photos from the tour and the tourist’s adventures. Overall, I would highly recommend this book to a history buff, a baseball historian, a transportation enthusiast, and anyone who loves a twisting and turning, yet realistic travel story.

Discover more from The Baseball Storyteller

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Baseball Book Review – Spalding’s World Tour By Mark Lamster”